Let’s get physical. In Part 9, I discussed some very easy gross observation tests you can use to determine the likelihood of substantial microbiological contamination (MC) in fuel tanks (nearly everything in this blog series applies to tanks of all sizes from power tool tanks (<1 gal) to refinery bulk storage tanks ( as large as 500,000 bbl).This post introduces a couple of very simple physical tests you can run on bottom samples to detect fuel system damage that might be related to uncontrolled MC (biodeterioration).

First, I’ll repeat something I’ve written previously: many individual biodeterioration symptoms are identical to the effects of non-biological processes. Do not draw conclusions from the results of any individual test. Treat each result as a piece of puzzle. At the same time, don’t forget: if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck… What makes identifying MC and biodeterioration different, is that most of us can recognize a duck when we see one. Few of us have been taught how to recognize biodeterioration when we see it.

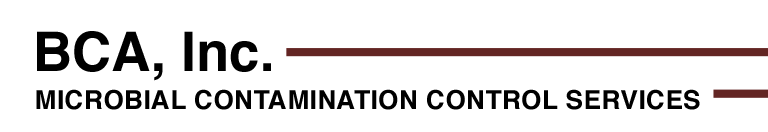

The first physical test I’ll review in today’s blog is rust. If you have no particles visible in your bottom-sample, there’s no need to run the test. However, if you see particles, a sludge/sediment layer, or if the sample contains opaque bottoms-water, this is a quick test to determine whether the sample contains rust particles. The one tool you need for this test is a magnet. I use a stirring bar retriever – a 12 in long, Teflon (Teflon is a registered trademark of Chemours’ polytetrafluoroethylene – PTFE) rod, that has a magnet at one end. You can also use an uncoated magnetic retriever or screwdriver with a magnetized head (both available at most hardware stores). You simply dip the magnet into the sample, gently swirl it around the sample bottle’s bottom, pull the magnet out of the bottle, and look at it. Compare what you see with the five examples shown in Fig 1. If the amount of rust is similar to that shown in photos 1 and 2, you probably do not have a corrosion problem. If you have lots of magnetic particles on the magnet (photos 4 and 5), then you most likely have a corrosion problem. Photo 3 suggests that there some corrosion, but it is not yet serious. Note: These photos are from bottom samples I took from a fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) tanks. Don’t forget that even FRP tank fuel systems have metal components that can rust.

The second test is just a bit more technical. To run this test, you’ll need a disposable, polypropylene, 50mL syringe; a 25 mm, in-line filter holder, 25 mm glass fiber filters, and a suitable waste receptacle for capturing the filtered fluid.

Step 1: place a glass fiber filer into the filter holder.

Step 2: remove the plunger from the syringe and attach the filter to the end of the syringe.

Step 3: dispense either 25 mL of fuel or 25 mL of bottoms water.

Step 4: Replace plunger into the barrel of the syringe and filter the fluid.

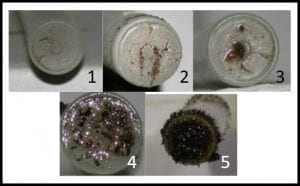

Step 5: remove filter from the filter holder and look at it; comparing its appearance with the illustrations in Fig 2.

Just as with Fig 1, the higher the score, the more likely you have substantial MC in the system.

Fig 2. Quick & dirty fuel particulate test. 0: clean; 1 & 2 moderate contamination;

3 through 5 heavy contamination.

Two quick and simple tests: One detects magnetic particulates and the other detects all particles that are trapped on the filter. A more formal version of the filtration tests includes weighing the filter before use, drying the filter and weighing it again after the residual fuel or water has evaporated off. After subtracting the filter’s original weight from its final weight and dividing by the volume filtered (sometimes you can push all 25 mL through the filter) you get particulate concentration in mg/mL. The lower the number, the better (ASTM D975 Specification for Diesel Fuel Oils; has a specification of ≤0.05 % by volume; this is ≤50 mg/mL).

These two physical tests build on the information you get from gross observations. If both the gross observation and physical test results indicate MC, then it’s a good idea to have a couple of chemical tests run. I’ll discuss these in my next post. If you are impatient and would like to learn more now, please send me an email at fredp@biodeterioration-control.com.