MICROBIOLOGY FOR THE UNITINTIATED – PART 4: MICROBIAL REPRODUCTION

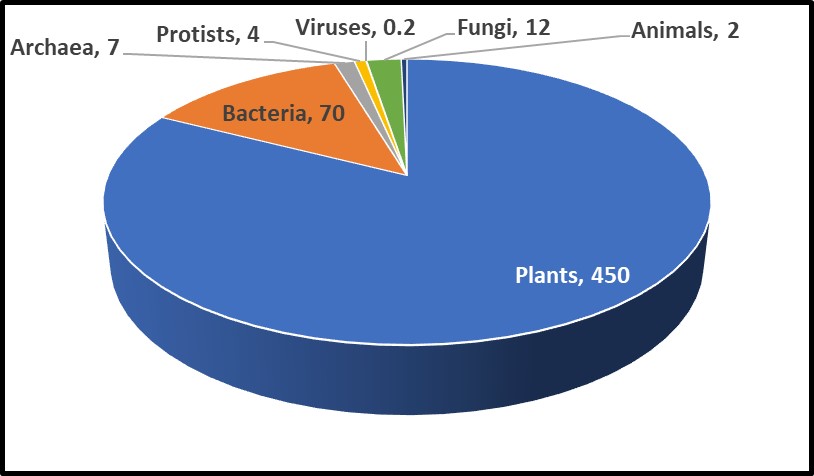

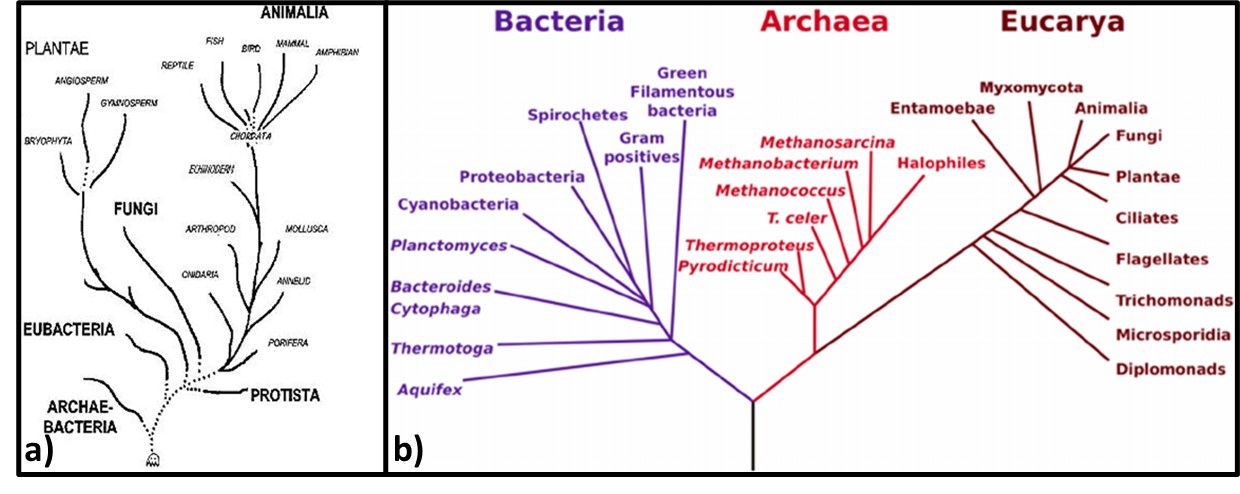

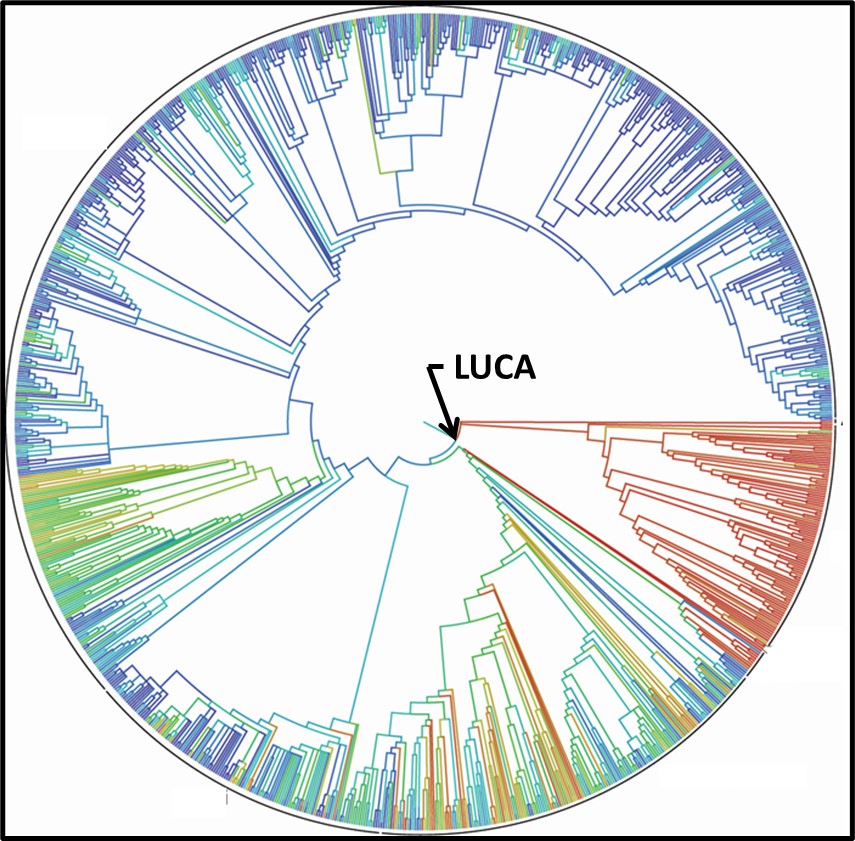

Tree of life

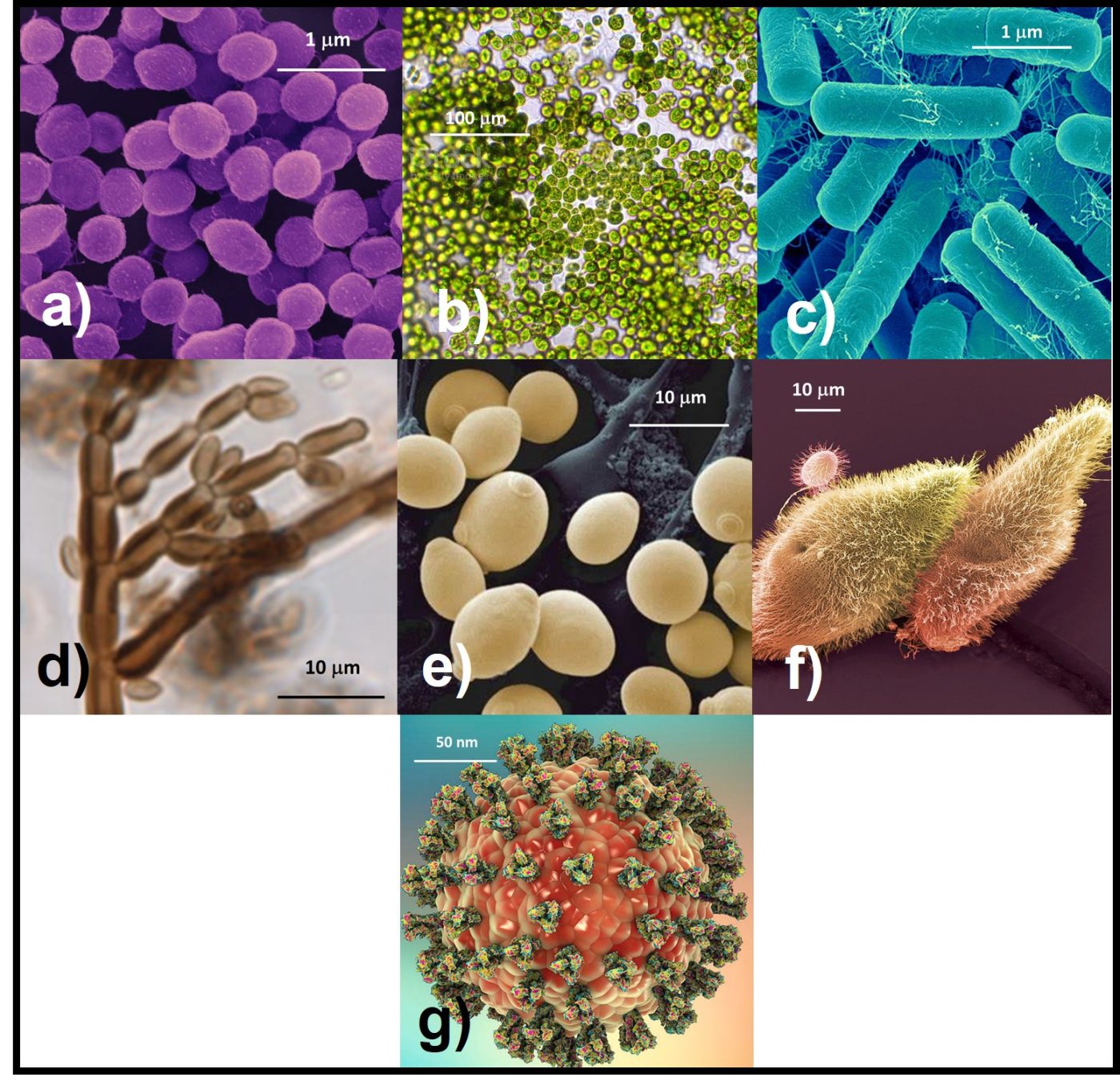

All Organisms Share Common Characteristics

As I explained in April’s column, all life forms share at least six common properties (variations of this list that include additional properties):

- Order

- Growth

- Homeostasis

- Metabolism

- Reproduction

- Respiration

In April I focused on order and growth. I followed with a discussion of homeostasis and metabolism in May. In this month’s article I will focus on reproduction.

Reproduction

The online Mirriam-Webster dictionary defines reproduction as “the process by which plants and animals give rise to offspring and which fundamentally consists of the segregation of a portion of the parental body by a sexual or an asexual process and its subsequent growth and differentiation into a new individual.” Were it not for reproduction, the first generation of a given type of microbe (or any other organism) would never be followed by a second generation.

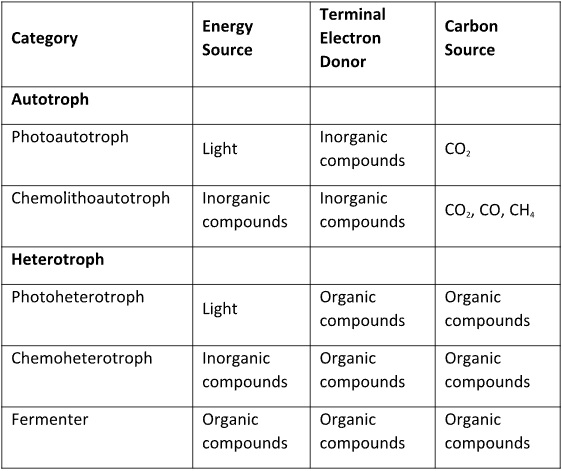

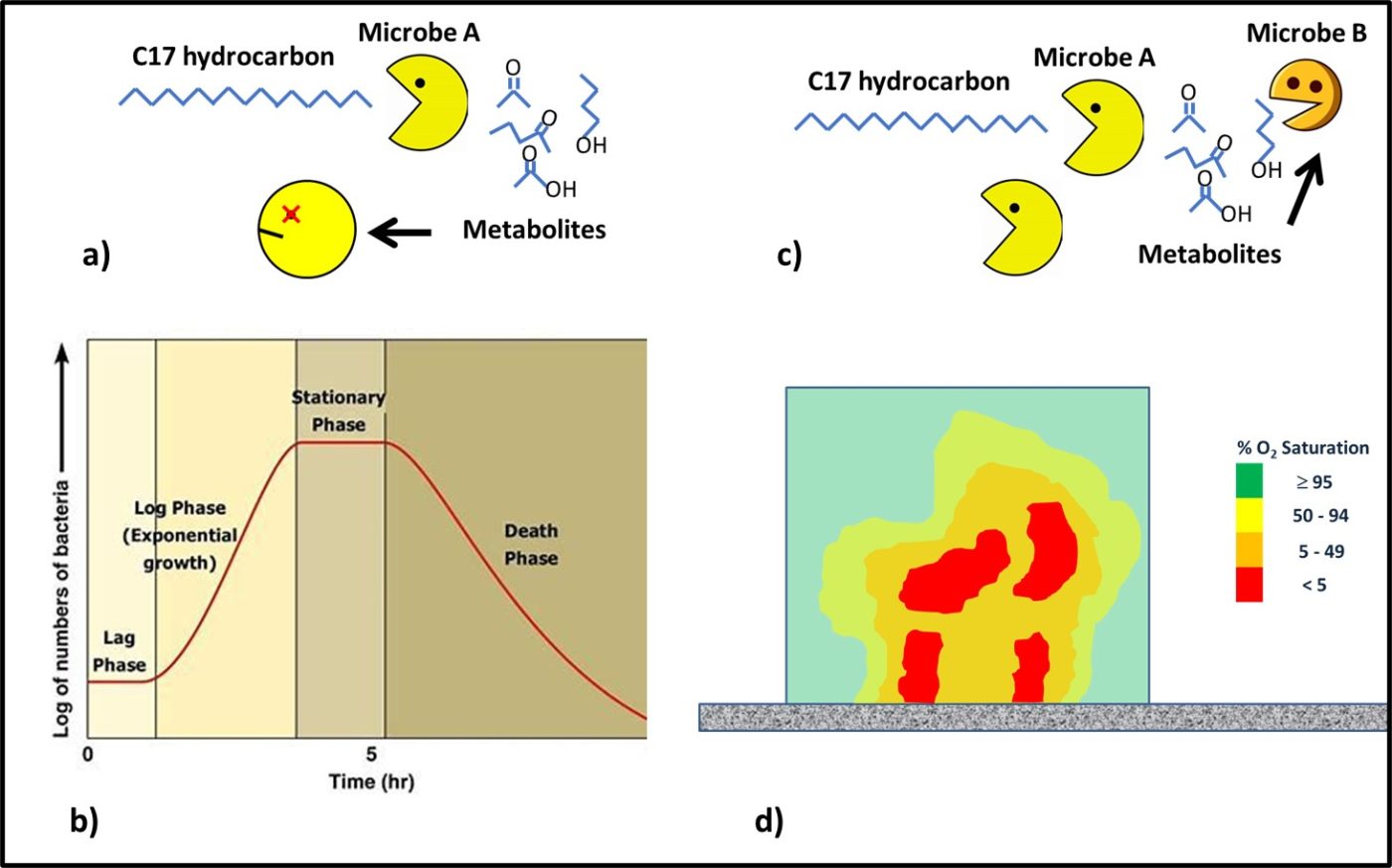

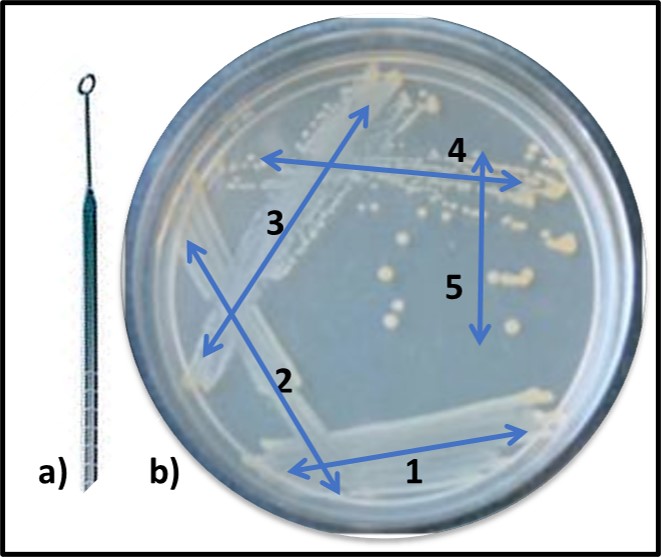

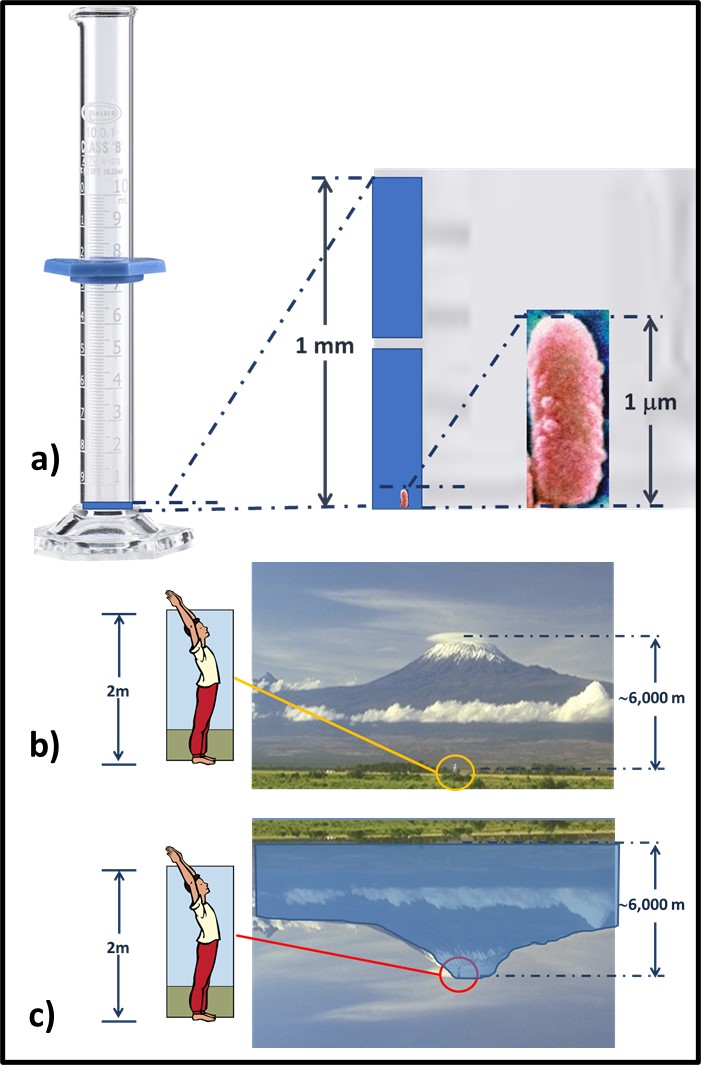

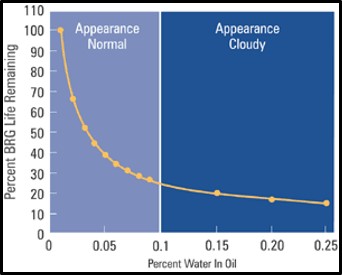

In previous posts, I’ve distinguished between growth (increasing mass) and proliferation (increasing cell numbers). However, in microbiology, it is common to refer to proliferation as population growth (or simply growth). The time required for the number of cells to double is called the generation time (G). As I discussed in my August 2021 What’s New article. In that article, I made the point that bacterial colonies typically become visible once they contain approximately 1 billion cells and that it takes 30 generations for one cell to proliferate into 1 billion cells (Figure 1; 230 = 1.0 x 109 – 1 billion). Figure 2 illustrates the slopes and 9.0 Log10 cells mL-1 endpoints for microbes that have generation times ranging from 0.5 h to 4 h. Reiterating the take home lesson from August 2021, if you are depending on culture test data, continue to record colony counts until they no longer change after an additional 48 h observation period. It is not uncommon for ecologically important microbes to have generation times that are 10 h or longer. Such microbes will require a week or longer to form visible colonies.

Fig 1. Bacterial proliferation – bacteria reproduce by binary fission. The time required for cells to divide is the Generation time (G). Once approximately 1 billion cells accumulate (30 generations) their aggregated mass is visible as a colony.

Fig 2. Exponential growth – impact of generation time (G) on time lapsed before a single cell multiplies through 30 generations. Bacteria with 30 min generation times can produce visible colonies within 15 h. As G increases, so does the delay between inoculation and colony visibility.

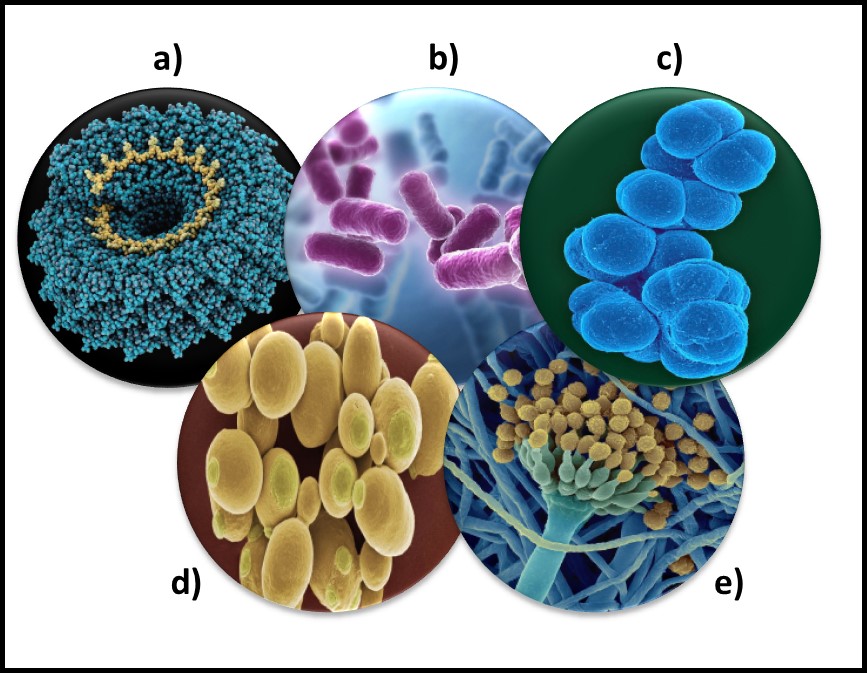

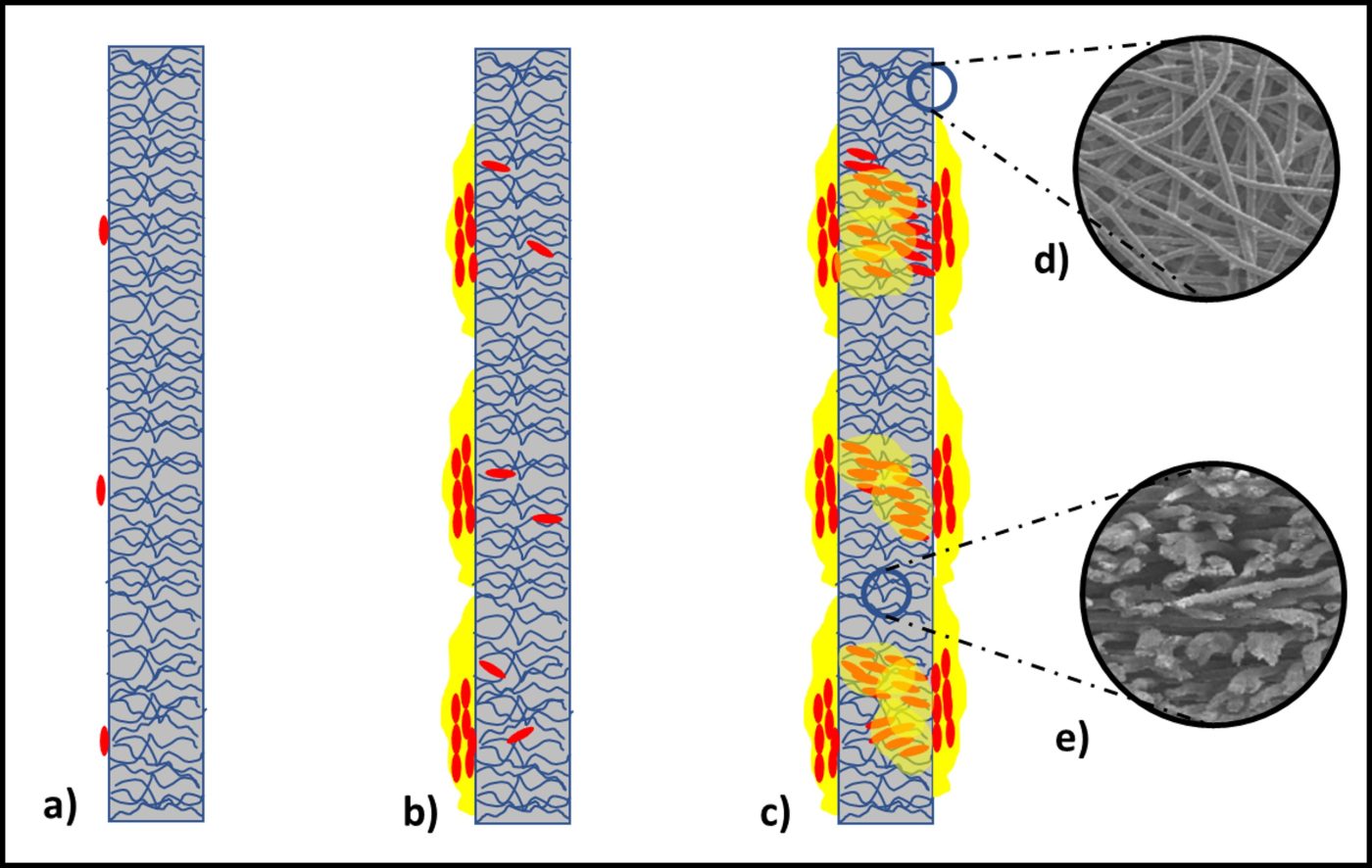

Bacteria – Bacteria reproduce by binary fission (Figure 3). As binary fission begins, the cell’s chromosome becomes visible when observed through a microscope (Figure 3a). Next, the cell wall and plasma membrane grow, and the chromosome begins to replicate itself (Figure 3b). Once the chromosome has duplicated itself and the two daughter chromosomes separate, a septum begins to form between the two cells (Figure 3c). The two daughter cells typically separate once the septation process is complete (Figure 3d). However, with some types of bacteria the cells do not separate. These microbes form chains or filaments (Figure 4).

Fig 3. Binary fission – a) chromosome condenses; b) chromosome replicates as cell wall and plasma membrane grow; c) newly formed replicate chromosomes separate while cell wall and plasma membrane begin to form a septum; d) once septum has formed, daughter cells separate. Adapted from Bacterial reproduction medical images for power point (slideshare.net).

Fig 4. Bacterial chains and filaments – a) Bacillus megaterium (rod-shaped bacterium) chain (source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/occbio/6414377511/); b) Streptococcus sp. (spherical – coccoidal – bacterium) chain (source: https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Streptococcus); Beggiatoa sp. sheathed filament (source: https://alchetron.com/Beggiatoa).

Fungi – Fungi reproduce either sexually or asexually. As discussed for bacteria, during asexual reproduction a cell replicates its entire complement of genes so that daughter cells each receive their genes from a single parent. In contrast, during sexual reproduction, the parents’ cell’s chromosomes separate (see below) with half of the genes going into each of two gametes. For some fungal species, gametes from different hyphae can combine. For others, gametes must come from two different colonies.

Unlike bacteria and archaea, fungi are eukaryotes – their internal structures, including the nucleus, are membrane bound. Consequently, fungal reproduction begins with either mitosis or myosis. After mitosis, the cell’s DNA is duplicated to that each daughter cell’s nucleus has a complete copy of the parent cell’s DNA. In this regard, mitosis is similar to bacterial binary fission.

There are three asexual fungal reproduction mechanisms:

- Budding – as illustrated in Figure 5, yeast cells most commonly reproduce by budding. The process begins as a yeast cell produces a bud. As the bud continues to emerge, the nucleus migrates towards the bud as DNA replicates by mitosis. The original (parent) nucleus divides and the two daughter nuclei migrate apart as one nucleus enters the bud and the other returns to the nucleus’ original location within the parent cell. As the bud matures, the cell membrane and wall develops until there are two separate cells. This process is called cytokinesis. The daughter cells can separate or remain attached to one another. If the latter occurs, the yeast cells can form chains or clusters.

- Fragmentation – cells in fugal filaments (hyphae) divide by mitosis. As shown in Figure 6, hyphae can elongate, form branches, or both as cells divide.

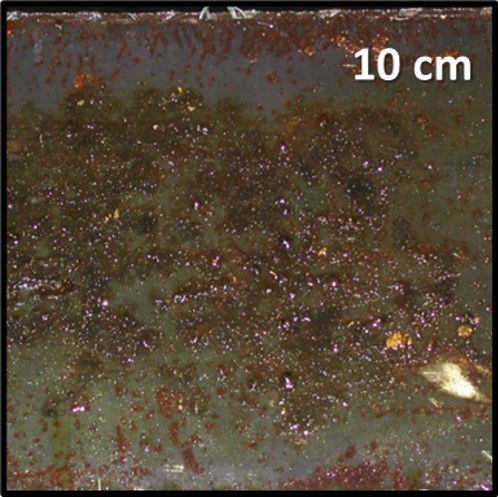

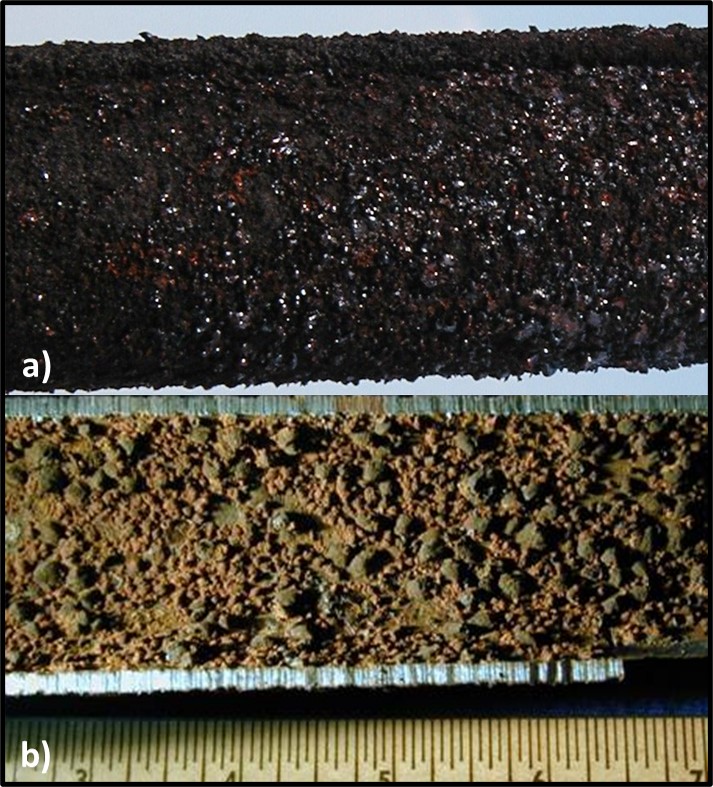

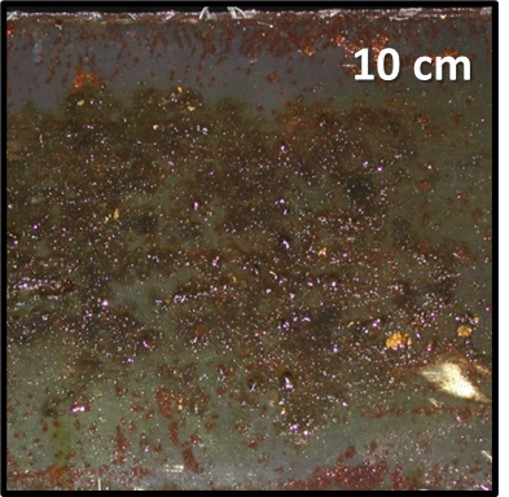

- Sporulation – filamentous fungi form specialized hyphae called aerial hyphae. Spores then form at or near the top of these areal hyphae (Figure 7). Spores formed by fungi such as Hormoconus resinae or Penicillium sp. that commonly grow in fuels or metalworking fluids are called conidia. These spores are pigmented and give fungal colonies their characteristic colors (Figure 8).

Fig 5. Yeast reproduction by budding – parent cell forms bud, cell’s nucleus begins DNA replication, once daughter DNA has been produced, the nucleus divides and the two nuclei migrate to the bud and parent cell respectively, the cell ultimately divides into two daughter cells which then continue to grow to maturity, after which each daughter cell will form one or more buds.

Fig 6. Filamentous fungus with fragmenting hyphae – note that as cells within filaments divide, filaments can elongate, branch, or both. Source: https://images.fineartamerica.com/images-medium-large-5/fungal-hyphae-dennis-kunkel-microscopyscience-photo-library.jpg

Fig 7. Penicillium colony with close up images of aerial hyphae and conidia.

Fig 8. Fungal colonies on growth medium. Different colors reflect characteristic pigmentation of each species’ spores. Source hold-breath-fungus-goes-airborne-easier-than-we-thought.w1456.jpg (1456×1092) (wonderhowto.com)

To reproduce sexually, gametes are formed in special hyphae. As I noted above, each gamete is haploid (i.e., contains a single set of chromosomes). Depending on the species, either two of these specialized hyphae from a single mycelium fuse or hyphae from two different mycelial masses (colonies) fuse. A pair of gametes then fuses to form a cell that contains two haploid nuclei. The two nuclei then fuse to form a diploid (i.e., paired chromosomes) zygote. Each zygote then divides to produce ascospores. When these ascospores disperse and settle onto suitable surfaces, they germinate and form new mycelia (Figure 9). This is a superficial explanation of fungal sexual reproduction. The details vary substantially among fungal species. The key point to remember is that sexual reproduction is the primary means by which genetic diversity occurs among fungi of a given species.

Fig 9. Fungal (Ascomycete) sexual reproduction cycle – specialized mycelial cells fuse to form a heterokaryotic cell – unmerged, haploid chromosomes from two gametes. The two chromosomes then merge to form a zygote. Zygote divides to produce spores. Spores germinate to initiate new mycelia.

Gene Transfer Beyond Reproduction

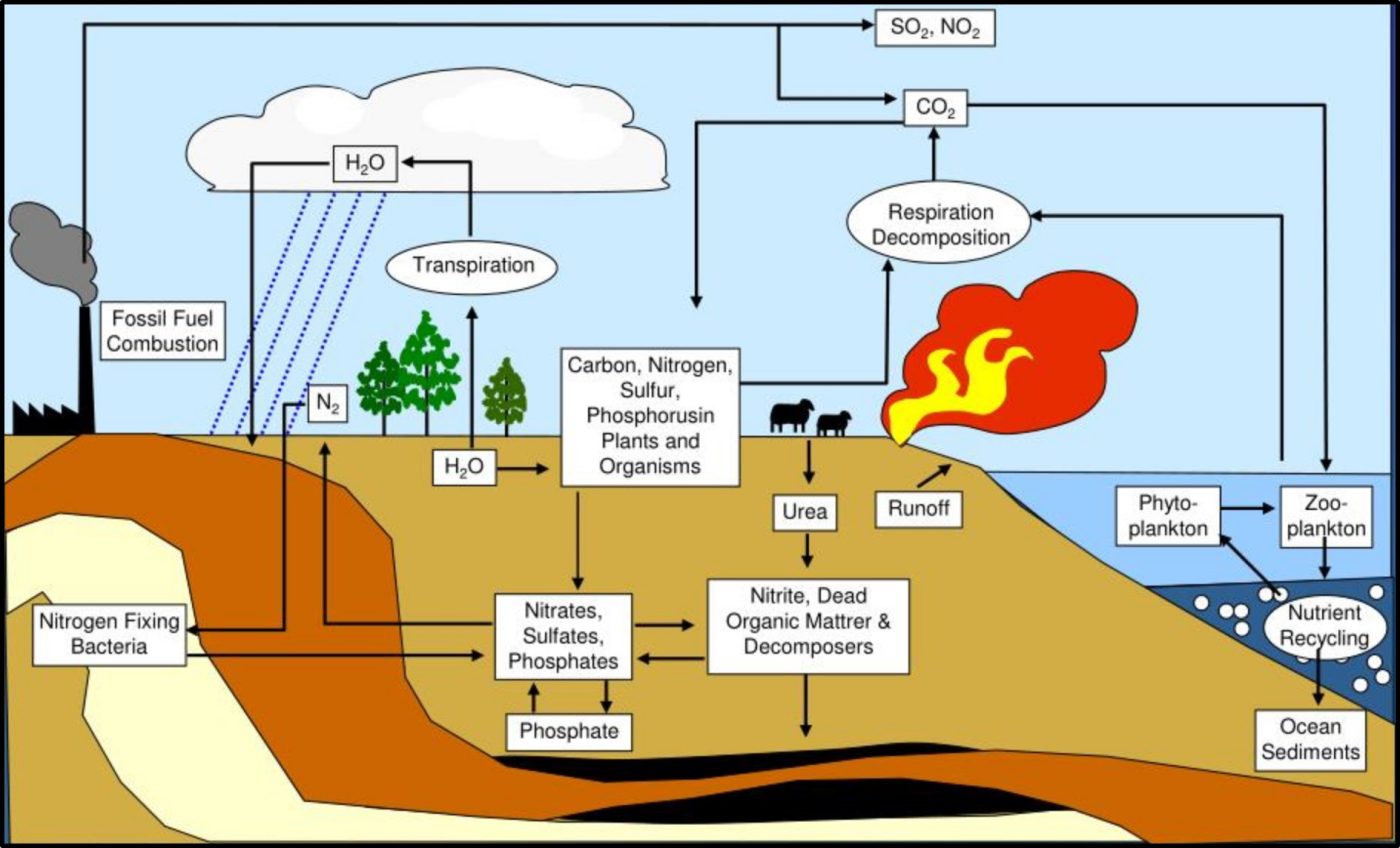

I often talk about promiscuity among microbes. This reflects the ease with which microorganisms transfer genetic material among cells within a microbiome. There are three primary mechanisms by which horizontal gene transfer occurs:

- Transformation

- Transduction

- Transfection

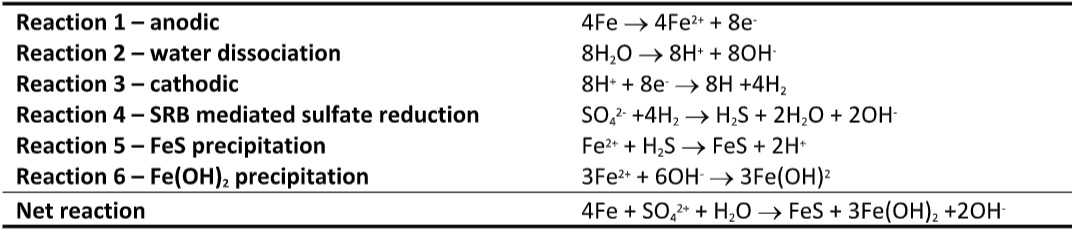

Transformation – a DNA fragment from a dead or damaged cell is released into the environment, enters another cell, and replaces a fragment of the receiving cell’s DNA. Typically, DNA fragments contain approximately 10 genes. Figure 10 illustrates the transformation process.

Transduction – a bacteriophage (type of virus that infects bacteria) transfers DNA from one cell to another. The process is illustrated in Figure 11.

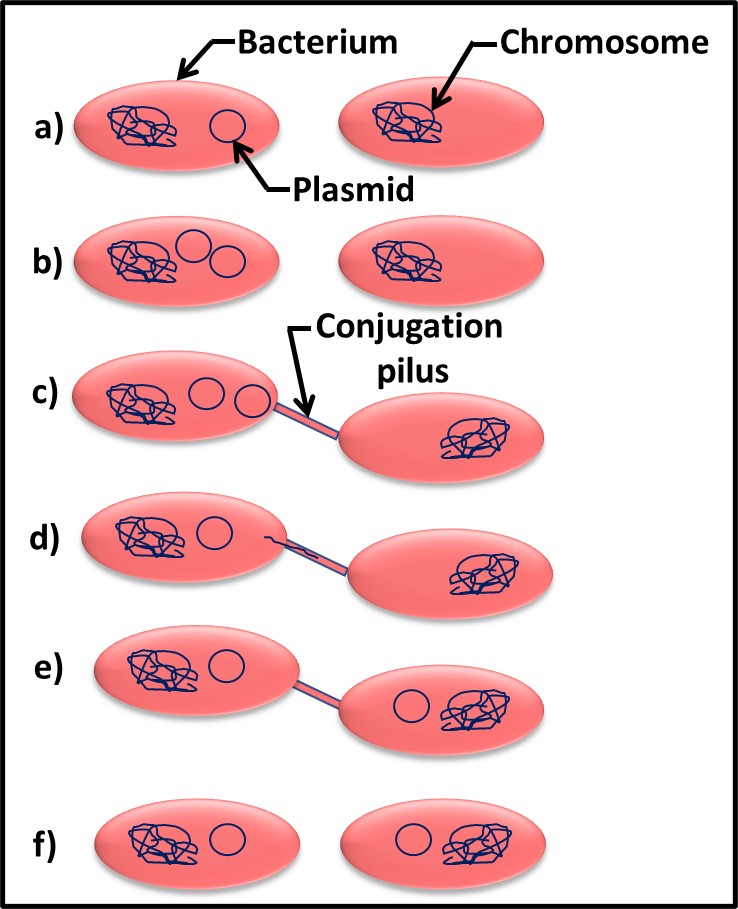

Conjugation – genetic recombination occurs when two cells attach to one another (in Gram negative bacteria, a sex pilus (tubular cell structure) links the cells and a DNA fragment (plasmid) transfers from one cell to the other. The plasmid can remain as extra chromosomal (i.e., not integrated into the recipient’s chromosome) DNA or be integrated into the recipient’s chromosome. One common plasmid that is transferred via conjugation carries genes responsible for microbicide (or antibiotic) resistance. Figure 12 illustrates conjugation.

Fig 10. Transformation: Step 1: A donor bacterium dies and is degraded. Step 2: DNA fragments, typically around 10 genes long, from the dead donor bacterium bind to transformasomes on the cell wall of a competent, living recipient bacterium. Step 3: In this example, a nuclease degrades one strand of the donor fragment and the remaining DNA strand enters the recipient. Competence-specific single-stranded DNA-binding proteins bind to the donor DNA strand to prevent it from being degraded in the cytoplasm. Step 4: RecA proteins promotes genetic exchange between a fragment of the donor’s DNA and the recipient’s DNA for the functions of RecA proteins). This involves breakage and reunion of paired DNA segments. Step 5: Transformation is complete. Source: Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bacteria

Fig 11. Transfection – a) A bacteriophage adsorbs to a susceptible bacterium; b) The bacteriophage genome enters the bacterium. The genome directs the bacterium’s metabolic machinery to manufacture bacteriophage components and enzymes. Bacteriophage-coded enzymes will also breakup the bacterial chromosome; c) Occasionally, a bacteriophage capsid mistakenly assembles around either a fragment of the donor bacterium’s chromosome or around a plasmid instead of around a phage genome.; d) The bacteriophages are released as the bacterium is lysed. Note that one bacteriophage is carrying a fragment of the donor bacterium’s DNA rather than a bacteriophage genome; e) The bacteriophage carrying the donor bacterium’s DNA adsorbs to a recipient bacterium; f) The bacteriophage inserts the donor bacterium’s DNA it is carrying into the recipient bacterium; g) Homologous recombination occurs and the donor bacterium’s DNA is exchanged for some of the recipient’s DNA; h) Specialized Transduction by Temperate Bacteriophage. Source: Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bacteria

Fig 12. Conjugation – Mobilizable plasmids, that lack the tra genes for self-transmissibility but possess the oriT sequences for initiation of DNA transfer, can also be transferred by conjugation if the bacterium containing them also possesses a conjugative plasmid. The tra genes of the conjugative plasmid enable a mating pair to form while the oriT sequences of the mobilizable plasmid enable the DNA to move through the conjugative bridge. Source: Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bacteria

Summary

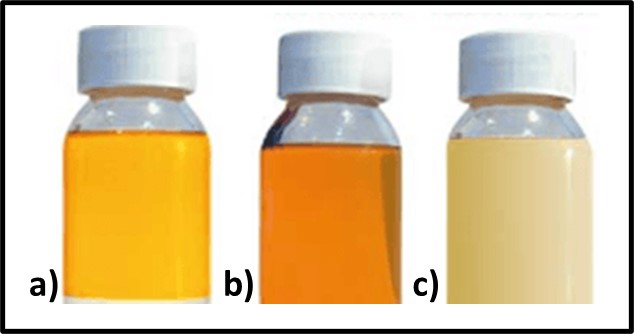

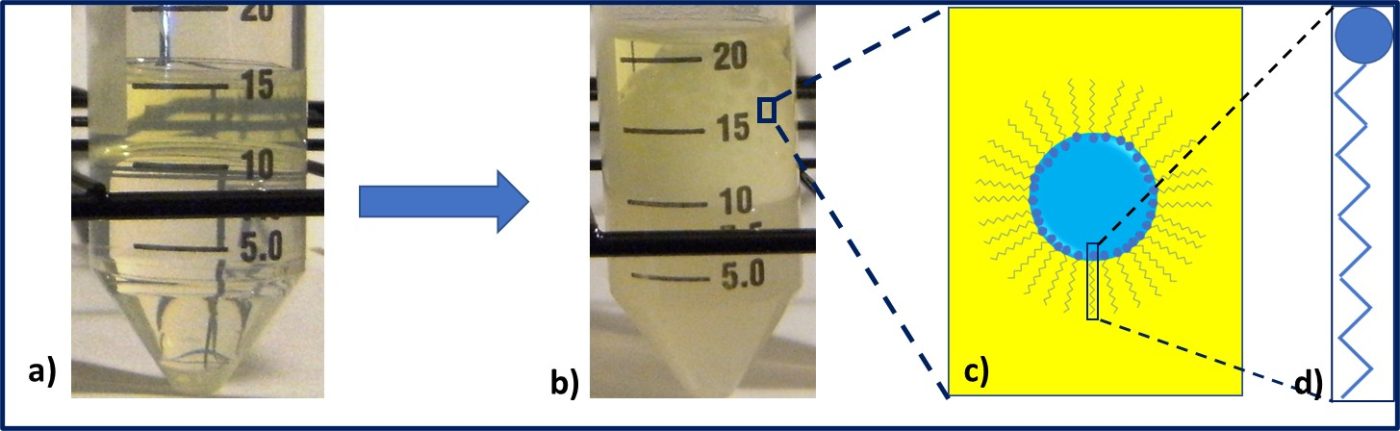

Reproduction is the means by which all organisms proliferate. Without reproduction, even a theoretically immortal cell would not have much impact on the environment in which it lives. The time required for a population to double is called the generation time. Colonies in or on solid nutrient media become visible after approximately 30 generations (one cell proliferates to approximately one billion – 109 – cells). Broth media typically becomes turbid when the population density is approximately one million (106 cells mL-1). This takes 20 generations (220 = 1.0 x 106). Bacteria reproduce asexually. Fungi can reproduce either asexually or sexually. An organism’s characteristics evolve when a successful mutation occurs, when DNA fragments are transferred among cells, or via sexual reproduction. But this is a topic for a future article.

For more information, contact me at fredp@biodeterioration-control.com.